The Department of Public Health (DPH) Little Free Library as an Environmental Justice Opportunity at Cal State LA

Evelyn Alvarez, MPH, PhD1, Naeomi Chin1,2, Nateli Franco1,2, Jade Hernandez1,2, Raquel Williams1,2*

1 California State University, Los Angeles. 5151 State University Drive ST 305, Los Angeles, CA 90032. 323-343-4748, evelyna@calstatela.edu

2 Cal State LA Public Health Student Association (PHSA)

*Corresponding author

About the Authors

Dr. Evelyn N. Alvarez1* is an associate professor of environmental health science in the department of Public Health at Cal State LA. Her research agenda largely focuses on web-based/smartphone environmental community science applications to address environmental waste, air pollution, and ‘green space deserts’. Her research also examines underrepresented narratives in the climate change dialogue and aims to demystify sustainability.

Naeomi Chin1,2 obtained her B.S. in Public Health from Cal State LA where she served as President of the Public Health Student Association (PHSA). She also was a cancer research intern at the Computational Biomedicine department at Cedars Sinai, where she focused on addressing health disparities and examining the environmental impacts on chronic diseases.

Nateli Franco1,2 is an undergraduate, Public Health major at Cal State LA. She is active in her campus community, serving as Vice President of PHSA and as peer health educator with the Student Health Advisory Committee (SHAC).

Jade Hernandez1,2 obtained her B.S. in Public Health from Cal State LA where she served as Treasurer of PHSA and was the Student Health Ambassadors committee lead for the Alcohol and Other Drugs Committee. Currently, she is an HIV/STD Enrollment Specialist with the JWCH Institute, Inc. + Wesley Health Centers where she aims to reduce barriers to healthcare access and help alleviate health disparities in underserved communities of Los Angeles.

Raquel Williams1,2 is an undergraduate, Public Health major at Cal State LA where she served as Vice President of PHSA and helped advocate for student wellness and health promotion. Raquel currently works at a psychiatric hospital in California where she directly works with patients, advocating for their mental health, and maintaining their safety.

Abstract

Winning the 2020 APHA Student Champions for Climate Justice award was an incredible honor for us. It got us thinking about what we could do to come together, create a sense of community, and make a difference on campus. Our team decided to create a Public Health Little Free Library (LFL) on campus to promote climate literacy, address book poverty, and to promote the idea of reading for fun as a way to ‘exercise’ our brains. In the spirit of scholarly service, we wanted to share our experience and the evolution of this grant project with a global audience. Receiving this award right before the COVID-19 pandemic stay-at-home orders added a layer of complexity and challenges that we had to tackle head-on as a team. We believe that the lessons learned will be valuable to those who are interested in doing similar interventions on their college campuses, and we hope this catalyzes an already growing movement to promote public health and climate literacy via little free libraries on college campuses worldwide.

Background

With Dr. Evelyn Alvarez as the project mentor, several Public Health Student Association (PHSA) executive board members brainstormed on the vision and planning of this project over the last few years. It was important to Dr. Alvarez that this project be student-led, but she was there every step of the way to help address challenges and to pivot towards a new, more tangible direction when the pandemic hit. Initially, since our campus is a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) and Minority Serving Institution (MSI), we decided that a Sustainability Film Festival, highlighting underrepresented narratives in the climate dialogue as well as increasing education about climate change, would be the project we would undertake. We were all very excited to launch this sustainability film festival but as COVID-19 sent us all home per lockdown orders, our project took a backseat. Little did we know how long that pause would be.

After realizing how long the remote phase of education would be due to the pandemic, the PHSA executive board at that time decided that doing this sustainability film festival online via Zoom would not capture the spirit of what we were trying to do. As a new PHSA executive board emerged, we decided that once we were back in person to a certain extent, we would continue the film festival planning. Unfortunately, we learned that even once we went back to face-to-face classes on campus at a limited level (with masks as a requirement), student group organizing in person was prohibited. This was done to try to minimize potential exposures. We then brainstormed on a new idea we could pursue that would not involve people coming together to attend a film festival. Out of these discussions, the Little Free Library (LFL) idea was born.

We decided to focus our efforts on creating an LFL on campus that would provide the campus community (faculty, students, staff, and visitors to the campus) with a place where they could pick up a free book and/or drop off a book they no longer need. The aim was to increase climate literacy by ensuring that we included books that promoted climate literacy, as well as books that are simply fun to read to promote the idea of ‘reading for fun.’ The impetus for this idea was the plethora of research that indicates how the brain benefits significantly from reading as it tries to process complex information from print to imagery, and how this can help community members protect their brains, prevent Alzheimer’s disease, and promote aging in place all while promoting climate literacy1,2. Reading has also been associated with a longer life as represented by a 20% reduction in mortality in those who read books compared to those who do not, thus conferring a survival advantage (HR = .80, p<.0001)3. Reading books, as opposed to periodicals, was also associated with a higher survival advantage3. This survival advantage was attributed to book readers’ attained cognition through book reading and not due to their baseline cognition3. Book reading was also found to be protective regardless of gender, wealth, health or education3. By including books on climate change, environmental health, and environmental justice and by circulating a call for more of the aforementioned books, we also hoped to promote climate literacy in our campus community.

We initially planned for the LFL to also be a place to drop off canned goods or fresh fruits and vegetables to create a ‘mini pantry’ but soon learned this was not going to be possible due to campus policies prohibiting the dispersal of food in this manner. We also planned on the LFL as a place to include free menstrual products to promote period justice as a form of environmental justice as access to these products can be costly, and we ideally wanted the LFL to serve multi-purposes. With the passage of the Menstrual Equity for All Act of 2021, Assembly Bill 2304, this was a moot point as the campus was now required to provide free menstrual products to all students on campus. This led us to keep the LFL as a book-only project.

Implementation Plan

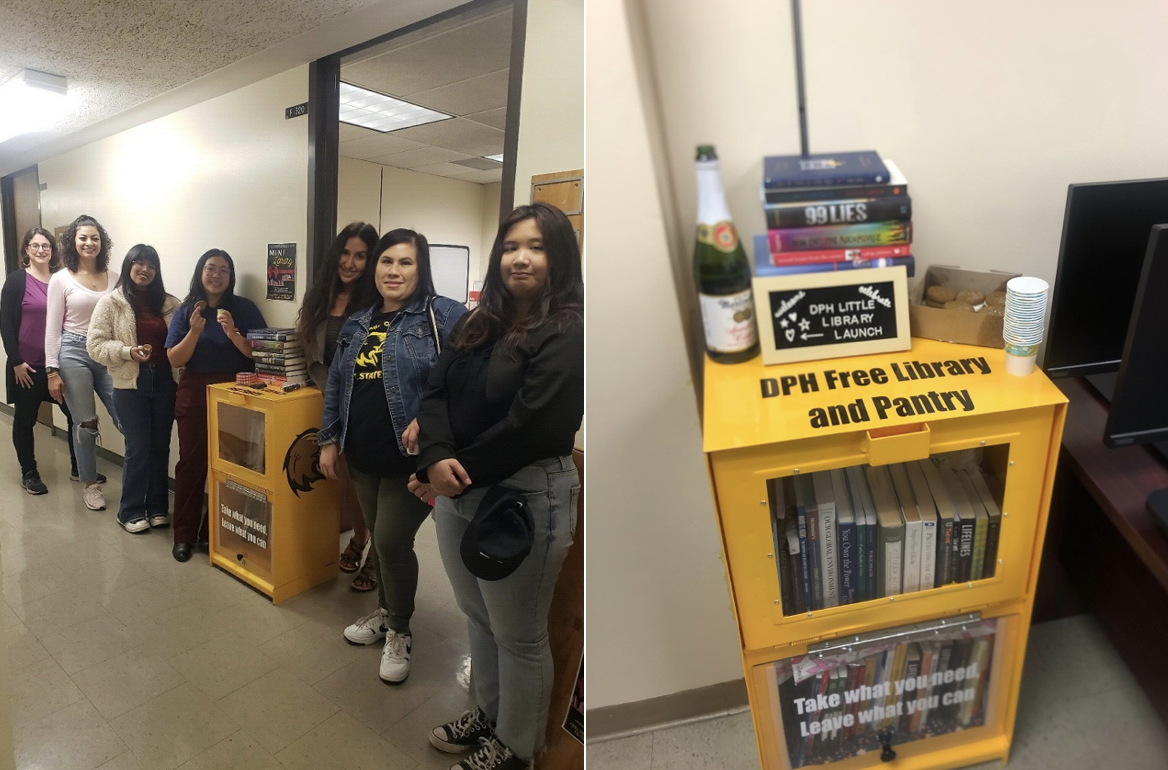

The LFL that we were so proud to put into use was not a simple process. Dr. Alvarez and PHSA worked tirelessly to design it, get its approval to place it on campus, and even hold a launch celebration to celebrate its existence. The LFL was acquired through a small business on Etsy, Impact Racks (a special shoutout to John for facilitating the purchase). The design of the LFL was meticulously crafted to align with the theme of increasing health literacy. The LFL is a refurbished newspaper stand painted in the school's colors of yellow and black, adorned with the PHSA logo on one side and the Cal State LA golden eagle mascot on the other. The plexiglass panes were inscribed with the inviting message, “Take what you need, leave what you can.” On March 23, 2023, the LFL was delivered and promptly moved to the third-floor hallway of Simpson Tower on campus, with assistance from PHSA members and other public health students.

The next hurdle was obtaining permission for the LFL’s installation. Initially, we had planned to place the LFL in a heavily trafficked area in front of the elevators in our department in Simpson Tower. However, complications arose over concerns about placing it in front of the elevators, which posed obstacles for wheelchair accessibility and safety. With this concern in mind, we devised alternative locations for the LFL in case this first location could not be approved. Our alternative locations included placing the LFL outside of Salazar Hall, in a location where there would be more foot traffic, or placing it next to Dr. Alvarez’s office. Determined to find a location for our LFL, Dr. Alvarez worked closely with the Risk Management department to find a suitable location. Risk Management dismissed our proposal to have the library outside due to vandalism risks and potential theft. We would not be able to place the library outside of Dr. Alvarez’s office because of the same concern regarding wheelchair accessibility. This led to consideration of placing the library in a staff member’s office as a temporary solution. The idea was to host the library in her office during daily office hours, from 8 am to 5 pm. Students would be able to drop by the office to pick up a book they wanted to read or drop off books in return.

Eventually, on December 4, 2023, an official launch and ribbon-cutting ceremony was held that over 20 faculty and students attended where we toasted with apple cider and cookies in a sustainable fashion without single-use plastic (see Figures 3–5 for photos of the LFL red-ribbon cutting ceremony, launch celebration, and relocation). While the inauguration celebrated overcoming the challenges of acquiring a location for the library and opening the project to our students, we were soon met with the unexpected circumstance of our staff member leaving her position, resulting in the LFL temporarily shutting down. Nonetheless, the library's presence was celebrated and promoted in the first DPH newsletter, marking a significant milestone despite the challenges. Fortunately, the LFL was eventually relocated to a permanent location inside the University Library (more on this in Relocation).

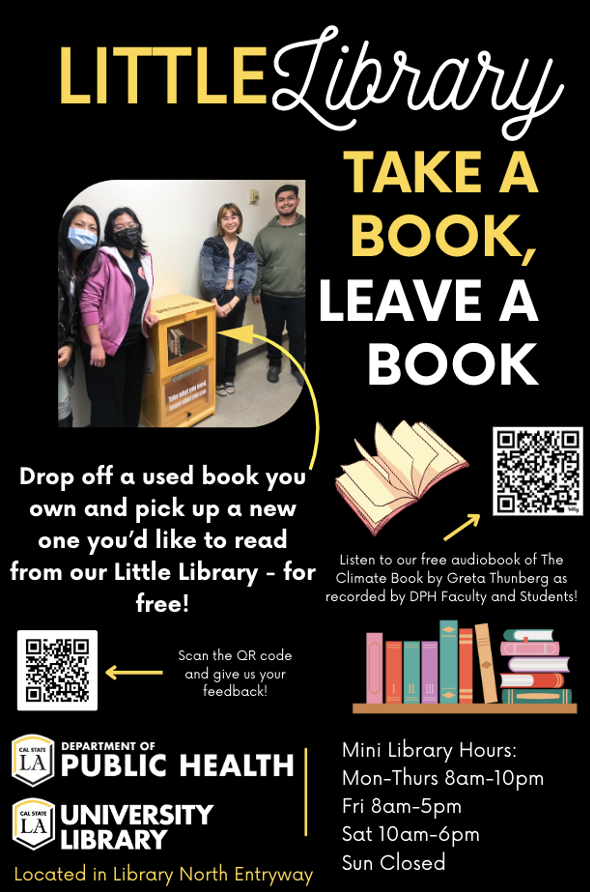

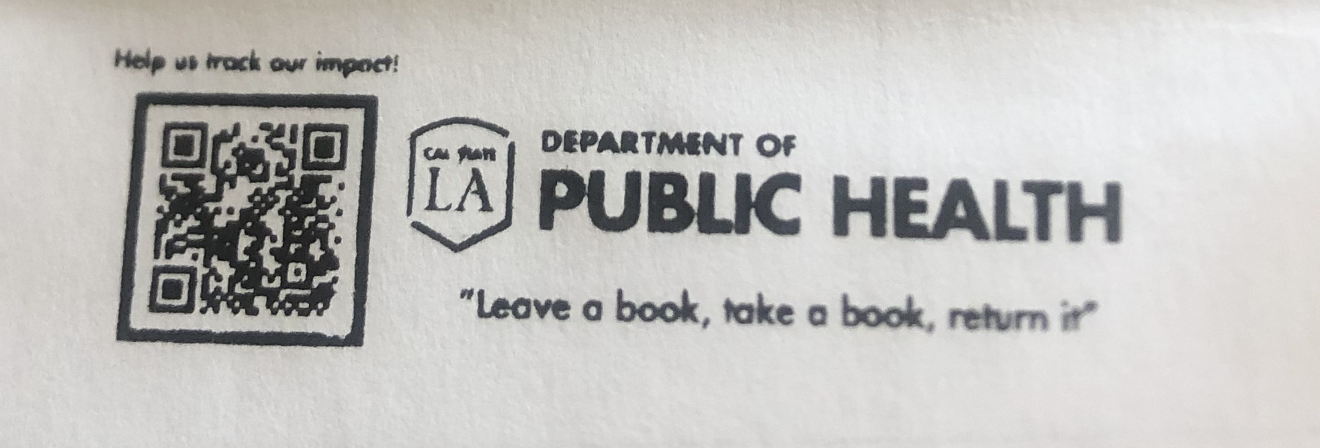

We also had to determine a way to track our impact as this is an environmental and public health intervention. Part of our implementation plan involved creating a way to track users’ thoughts on the LFL, how often they use it, and what suggestions for improvement they would like to see. We decided to create a survey using Google Forms to acquire this feedback, and we included a QR code to access this survey on our advertisement materials (see Figure 1). The QR code provides a way for community members to leave feedback on their experience using or donating to the LFL. We also created a stamp (see Figure 2) that includes the QR code as well as our project slogan, “Leave a book, take a book, return it” to be stamped in every LFL book. Preliminary feedback indicated a desire to see more women’s empowerment and women’s health books as well as more hardback and classical literature books. We continue to collect that feedback and are in the process of analyzing it, as well as advertising a call for more of the requested books via our social media channels. We also look forward to using this data to publish on its uptake, as well as to find additional funding mechanisms to help it grow even more.

Equally important for our implementation plan was to make sure our signage clearly indicated that although this was an interventional structure inside the library, it is still separate from the library. We laminated a sign that is posted on the front of the LFL that clearly indicates that library books cannot be dropped off in the LFL. We have an amazing library system on campus and we wanted to make sure that the normal process of checking out and returning library books was not obfuscated by the existence of our LFL, which is a supplement to the extensive array of library books available to our campus community.

Relocation

In a positive turn of events, Dr. Alvarez collaborated with the University Library Dean and in February 2024, Dr. Alvarez and Nateli relocated the LFL to its permanent location in the university's main library entryway. The LFL was placed alongside a Free Seed Library, another little library project that aims to promote gardening, food justice, and seed saving5. This partnership not only resolved placement issues but also integrated the PHSA initiative into a central academic space, ensuring that the LFL is accessible to all students, becoming a self-sustainable method of encouraging health literacy within our community. The University Library also made a webpage for the LFL to provide a guide to the campus community as to how to use it6.

The DPH Audiobook of the Climate Book

One of the most noteworthy highlights of the 2023–2024 academic year for DPH and PHSA has been organizing the Public Health Department-wide ‘Book Read’ event series on campus, which, under the direction of incoming department chair at the time, Dr. Gregory Stevens, brought an array of very special guests (Sammy Roth of the LA Times, Caleigh Wells of KCRW, mark! Lopez (spelled as written) of East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, and environmentalist-author Bill McKibben) to Cal State LA for conversations on topics such as Public Health activism, climate dread, environmental justice, and tackling climate change as a collective7,8,9,10. For this year’s Book Read event series, we chose Greta Thunberg’s The Climate Book, and created a free audiobook with select chapters read by DPH faculty and students11. A QR code for this audiobook can be found on flyers and posters promoting the LFL, which were actively posted on campus and on PHSA’s social media channels (see Figure 1). In line with PHSA’s mission to provide all Cal State LA students with information on public health-related opportunities, the DPH & PHSA audiobook is one more way to promote health literacy, making public health issues and climate topics more accessible to our campus community.

Takeaways

To recap, we wanted to conclude with key takeaways from this project that can serve as a model for small-scale, high-impact interventions elsewhere.

Firstly, be ready to pivot. We had initially planned on hosting an environmental film festival to raise educational awareness about environmental justice issues, but we had to reconvene and brainstorm again due to the pandemic. It is important to keep in mind that reinventing your project does not equate failure, especially when something like the COVID-19 pandemic hits us. Keep your team focused on the main project goal, which in our case was to promote climate literacy and tackle book poverty as a public health resilience strategy. Armed with knowledge about climate change and with miscellaneous fiction and non-fiction books, our campus community can be more climate aware and also enjoy the health benefits of leisure reading.

Secondly, be respectful of the delicate intricacies of a university bureaucratic system. Understand that all college campuses have different policies when it comes to placement of structures on campus. Respect that it will be a long process to get the necessary approvals to put in place an interventional structure on campus. This may involve meetings and correspondence with key stakeholders including administrators and other staff. During the early stages of the pandemic, in-person meetings and events were prohibited for very legitimate and public health related reasons. It is important to find alternative ways to meet to push forward your project, which may include relying on e-mail and Zoom during public health related emergencies.

Thirdly, have an implementation plan. Determining a space for your LFL or any other structural intervention is only one part of a project. It is key to have a clear implementation plan that prescribes a step-by-step chronology of your project. For us, it was crucial to find a location for our LFL first, followed by establishing proper signage and advertisement to increase uptake, and to determine a way to track our impact by collecting feedback in a standardized way. All stakeholders of your project, whether it is an LFL, or any other public health related project, should have a clear understanding of this implementation plan.

Lastly, find allies and partners – you cannot do this alone. It may seem like a small project at first, but any ongoing intervention that becomes a permanent campus installation requires time and dedication. One person cannot do this alone. It is important to leverage help from your village – whether it is your student association, your faculty colleagues, your chair or dean, it is critical to let all parties know of your project (by disseminating a press release, posting flyers all over campus, contacting the student newspaper, conducting a red-ribbon cutting ceremony to commemorate event, etc.) so as to gain support for it. Your campus library administrators and librarians (in our case we are indebted to them as they have played a critical role in this project) are other key players that could potentially offer advice or help in setting up a book-related project. In our case, we partnered with our University Library Dean to find a permanent location for our library, and we have also recently partnered with our campus librarians who created a helpful webpage for our LFL13. To further illustrate the power of our village, we have also recently obtained a donation of an elegant tablecloth from our university’s catering department which helps to conceal the dead space under the table on top of which our LFL is now situated. Reach out to different departments on campus that could help to provide small items that you need to carry out your intervention. You never know who is willing to help until you ask.

The LFL is here, and it’s our village’s handful of soil.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our funder, the American Public Health Association (APHA), for the Student Champions for Climate Justice award that enabled us to bring forth such a valuable public health campus intervention.

Figures

Photo Credit: Dr. Alvarez and Dr. Sabado-Liwag

Photo Credit: Dr. Alvarez and Dr. Sabado-Liwag

Photo Credit: Dr. Alvarez

[1] Hughes TF, Chang CC, Vander Bilt J, Ganguli M. Engagement in reading and hobbies and risk of incident dementia: the MoVIES project. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010 Aug;25(5):432–8. doi: 10.1177/1533317510368399.

[2] Alvarez, E.N. (2023). Infectious Diseases and Healthy Ageing: Making the Case for a 15-Minute City. In: Asiamah, N., et al. Sustainable Neighbourhoods for Ageing in Place. Springer, Cham. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41594-4_10][0]

[3] Bavishi, A., Slade, M.D., & Levy, B.R. (2016). A chapter a day: Association of book reading with longevity. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 164, 44–48. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.014][1]

[4] H.R.3614 - 117th Congress (2021–2022): Menstrual Equity For All Act of 2021. (2022, November 1). [https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/3614][2]

[5] California State University, Los Angeles. Cal State LA Seed Library. (2024). [website] [https://libguides.calstatela.edu/c.php?g=1336844&p=9889875][3] (Accessed September 6, 2024).

[6] California State University, Los Angeles. Cal State LA Little Free Library (LFL). (2024). [website] [https://libguides.calstatela.edu/freelittlelibrary][4] (Accessed September 6, 2024).

[7] Stevens, G.D. (2024). A Series on Climate Change and Hope. The Medical Care Blog. [https://www.themedicalcareblog.com/climate-change-and-hope/][5]

[8] Alvarez, E.N., Chin, N., Hernandez, J., Stevens, G.D. (2024). Every Little Bit Helps: On Climate Change and Hope With Sammy Roth and Caleigh Wells. The Medical Care Blog. [https://www.themedicalcareblog.com/every-little-bit-helps/][6]

[9] Hernandez J, Chin N, Alvarez E.N., Stevens G.D. (2024). First, Love Your Community: On Community Environmental Activism With mark! Lopez. The Medical Care Blog. [https://www.themedicalcareblog.com/first-love-your-community/][7]

[10] Chin N, Hernandez J, Alvarez E.N., Stevens G.D. (2024). Be a Little Less of an Individual: On Climate Change with Bill McKibben. The Medical Care Blog. [https://www.themedicalcareblog.com/lessofanindividual/][8]

[11] California State University, Los Angeles, Department of Public Health. (2024). [YouTube Channel] [https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLXAS9SYPVx5ejqseDrFHNx0-cGdUvKMaM][9] (Accessed September 6, 2024).

[12] California State University, Los Angeles, Public Health Student Association (2024) ‘Breaking News’ [Instagram]. 22 April. Available at [https://www.instagram.com/p/C3rOMz_LSeO/?img_index=1][10] (Accessed September 6, 2024).

[13] California State University, Los Angeles (2024) ‘Free Little Library’ [website]. Available at https://libguides.calstatela.edu/freelittlelibrary (Accessed September 6, 2024).

The Public Health Student Association at Cal State LA, guided by Dr. Evelyn Alvarez, created a Little Free Library to promote climate literacy and encourage reading on campus. The project began after the pandemic disrupted earlier plans for a sustainability film festival. Students and faculty worked together to design and install the library, which features books on climate change, public health, and leisure reading. It was first placed in Simpson Tower and later relocated to the University Library for greater accessibility. Community members can take or donate books, and a survey with a QR code collects feedback to track its impact. The project highlights the importance of adaptability, collaboration, and creative public health interventions that support literacy, environmental awareness, and student engagement.