Medics in the Crosshairs: The Syrian Regime’s War on Healthcare

beier nelson

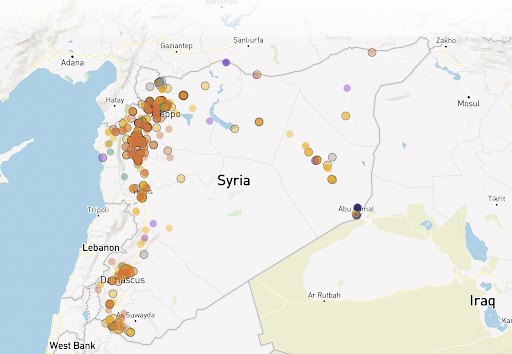

A map marking the locations of attacks on healthcare facilities in Syria between 2011-2022.

Source: https://syriamap.phr.org/#/en

Introduction

The ongoing Syrian Civil War has become one of the deadliest conflicts in the twenty- first century, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians, an international refugee crisis, and global condemnation of Syria’s Assad regime.1 Beginning in 2011, the Syrian Civil War originated as a series of nationwide protests against the long-ruling Assad family as part of the larger Arab Spring movement, in which citizens of various Arabic and North African countries agitated for democratization of their native governments. Spurred by discontent with the autocratic government, widespread corruption, and a stagnant economy, the regime chose to crack down on the protestors with violent force, escalating into a civil war between the government and opposition forces. During the war, the Assad regime became notorious for besieging civilians, using chemical weapons, and deliberately targeting hospitals and healthcare workers, the focus of this paper. Between 2011 and 2020, there were 595 attacks on healthcare infrastructure, 536 of which were conducted by the Syrian government and the Russian Air Force, leading to the deaths of 923 medical personnel.2,3 By 2021, half of all health facilities in the nation were destroyed, and 70% of surviving healthcare workers have fled the country. These attacks on health infrastructure are prohibited under the Geneva Conventions of 1949; Article 19 of which states that “fixed establishments and mobile units of the Medical Service may in no circumstances be attacked, but shall at times be respected and protected by the Parties to the conflict.”4 In an effort to maintain power over both the opposition and the civilian population, the Assad regime violated international law, initially using surveillance and intimidation tactics on protestors and healthcare workers and later escalating to direct military action on healthcare facilities. The regime justified their systematic targeting of the Syrian healthcare sector during the conflict as counter-terror measures, treating healthcare workers akin to the rebel opposition they were determined to eliminate.

Rising tensions in healthcare in pre-war Syria

The weaponization of healthcare during the Syrian conflict was enabled by the pre-existing structure of the nation’s health delivery system as the centralized healthcare decision-making allowed for widespread surveillance of the population.5 As the main providers of care, the Syrian Ministry of Health’s 90 state-run hospitals comprised half of the total hospital beds in the nation in 2010, with the flagship hospitals located in Aleppo and Damascus, Syria’s largest cities. Although private hospitals were present, government-run hospitals offered free healthcare to its patients, serving as a double-edged sword as access to health was improved but more Syrians became under the watch of the government. In the initial anti-government protests in 2011, the Assad regime utilized this aspect of the healthcare system to target protestors as security forces stationed at hospitals detained patients suspected of being involved in protests. Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) documented an instance where security forces attempted to arrest a sixteen-year old male in a hospital’s emergency room because he suffered a spinal cord injury.5 Furthermore, a certain Dr. Karim—a surgeon at a government-run hospital—recalled that the surgical team would attempt to hastily discharge a patient because “the police would come to see where he came from and how he got injured.”5 From the start of the conflict and even to when the pre-existing healthcare system was designed, the Assad regime understood the importance of using healthcare as a chokepoint to maintain power over the civilian population.

Detention of Healthcare Workers

As state-run hospitals became increasingly unsafe, many medical activist organizations created makeshift field hospitals to provide basic emergency medical services to injured protesters, resulting in the Syrian government detaining healthcare workers en-masse in response.5 According to a 2021 PHR research report, 1,644 healthcare workers were detained from 2011 to 2012 (there were 1,685 detentions in total as some workers were detained multiple times), including 614 physicians, 397 health-sciences university students, 113 nurses, 111 pharmacists, as well as dentists and veterinarians.5 Because these healthcare workers were the protestors’ literal and figurative life support, the Syrian government viewed healthcare workers as a greater threat than the ordinary protestor; a case study of 299 detained healthcare workers revealed that 64.5 % of the workers “were detained for providing medical care” while only 33.5% “were detained due to their involvement in political activities, including participating in protests.”5 By severing the ability of healthcare workers to treat the protestors, the Assad regime hoped to maintain control and weaken the opposition movement, employing the classic “shoot the medic” strategy. Furthermore, of the 1,685 recorded detentions, 1,133 healthcare workers were forcibly disappeared, which PHR defines as “the government depriv[ing] the detainees of their liberty without a legal proceeding or official recognition that the disappearance had taken place.”5 In contrast, there were only 15 cases in which the Syrian government publicized the detention of a healthcare worker.5 Paradoxically, the secretive nature of the detentions only added to widespread fear they caused, a common strategy employed by the Assad regime throughout Syria’s modern history. For example, the 1982 Hama massacre against the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood resulted in the deaths of several thousand civilians, but the event was never publicized by the Syrian media, wo news of the massacre only spread via word of mouth from those who fled the city.7 In a similar manner, the Syrian regime capitalized on the uncertainty caused by the disappearance of healthcare workers, inducing fear in the larger healthcare worker population when one of their colleagues goes missing and thus intimidating them to stop providing care. Human rights violations of detained medical personnel: a case study This fear is not irrational; the treatment of detained Syrian healthcare workers is on par with the most notorious human rights violations for which the Assad regime is internationally condemned. PHR acquired first-person accounts from a one story detailing three university students working for the Noor al-Hayat, a medical organization that provided emergency treatment to wounded protestors in Aleppo.5 On June 17, 2012, the three students—Abdullah, Hassan, and Ibrahim—were returning from a shift at a protest when they were detained at a security checkpoint by governmental forces for possessing a medical kit in the vehicle. Later that night, Hassan’s parents received a call from their son’s phone in which the voice of a governmental soldier threatened, “You did not know [how] to educate your child, we will do that for you.” Six days later, Ibrahim’s parents received a call that directed them to the site of a car in which laid the burnt corpses of the three students. A close friend of the students recalled that upon closer inspection, “there were signs of beating and torture by flogging on [Hassan’s] back” and that “he had a gunshot wound behind the left ear.”5 It is plausible that the security forces may have been “bad apples” and were operating out of pure malicious intent, but the Assad regime has been infamous for combining intimidation tactics with sadism. Although this horrific action by the security forces was meant to terrorize the healthcare workers into submission, it had the opposite result as the killings of the three students escalated the protests and hardened the resolve of many healthcare workers.5 Unfortunately, a vicious cycle began as the Syrian regime became more violent when their initial actions to maintain power did not result in the consequences they wanted.

Military action against healthcare personnel

As the uprising unfolded into a full-scale civil war, the Syrian government’s intimidation tactics on healthcare workers progressed into direct military action against the entire healthcare sector.8 These attacks included but were not limited to the use of snipers against clearly marked medical personnel as well airstrikes on hospitals and ambulances. In one instance documented by the UN Human Rights Council, a Red Crescent worker was killed by a sniper positioned only 200 meters away; the assailant was able to clearly distinguish the worker’s medical uniform.8 Furthermore, most of these attacks took place in areas held by opposition groups and contested areas, signifying the regime’s willingness to escalate their human rights violations to assert power.10 In an interactive map published by PHR marking all of the attacks on healthcare facilities from 2011 to 2022, an overwhelming majority of the attacks were located along the Western edge of the country, with the Aleppo, Idlib, and Damascus governates—regions with a strong opposition presence—hit the hardest.9

In addition to hospitals, ambulances were also attacked, with 243 ambulances targeted between 2016 and 2017; in 2016, 87% of the attacks occurred in regions held or partially held by armed opposition groups, while only 1% of the attacks occurred in government-controlled areas.11 The “double-tap” strategy is often used by the Syrian governmental forces when attacking healthcare infrastructure, sending a second airstrike directed at the same location a few minutes after the first, ensuring that the infrastructure is destroyed as well as killing any healthcare workers providing care to the wounded after the first strike. In 2016, minutes after wounded civilians were transported to a hospital in East Aleppo following an airstrike at a nearby school, the hospital “was assaulted by two additional airstrikes 5 minutes apart, killing 55 people and damaging the hospital’s ambulances and infrastructure.”10 Whereas the regime could still utilize healthcare as a means of surveillance in government-controlled areas, they felt a need to destroy health infrastructure in areas where the regime had less control to weaken any means of the opposition’s support. Indeed, a 2013 United Nations Human Rights Council Report summarized that the regime “deliberately target[ed] medical personnel to gain military advantage by depriving the opposition and those perceived to support them of medical assistance for injuries sustained.”8 The transition from initially utilizing the healthcare system to track dissenters to outright bombing their own hospitals exposes the regime’s desperation as their power becomes fragmented by the conflict.

Justification by the Assad regime

These actions by the Syrian regime are unjustifiable in under international law; hence, Assad and his supporters have self-justified these atrocities to maintain control over the country. To legally justify their intimidation of healthcare workers in the early stages of the conflict, the Syrian regime passed a “counter terrorism law” in July 2012 “effectively criminalizing the provision of medical care to anyone injured by pro-government forces in protest marches against the government.”12 The argument that the anti-government protestors are “terrorists” provided the regime with a twisted moral justification to continue to use their own terror tactics to target healthcare workers to maintain power. As the war progressed and the provision of healthcare to the opposition forces became a factor in the regime’s diminishing power, the regime began to view healthcare workers as combatants that must be eliminated. In Assad’s Opera House Speech in January 2013, he justified this assault by scathingly denounced his opposition as “enemies of the people”, “criminals”, and “terrorists instilled with al-Qaeda thought,” using a nationalistic framing around which he and his supporters can rally.13 Assad is also attempting to checkmate the West, emulating the U.S-led stance on terrorism to justify attacking his opposition—civilian healthcare workers and health infrastructure included. In the end, the regime’s self-justifications enabled Assad to leverage “counter-terrorism” and “national security” to commit atrocities and violate international law to maintain power.

Current status of healthcare workers in Syria and future implications

As of 2022, the Assad regime has regained near full control of the nation, and attacks on hospitals have died down; there have only been 8 confirmed hospital attacks by the regime since 2020 and no attacks reported in 2022.9 Most of these attacks occurred in the Idlib governate in the northwest, where Syrian governmental forces launched a campaign in 2019 to suppress the opposition foothold in the region, once again revealing the regime’s willingness to target healthcare to retake control.1 However, because these are recent numbers, the official reported number of attacks may be an underrepresentation as investigations may still be underway. As the regime regains control, it will hopefully reduce its attacks on healthcare facilities, as it will need any remaining hospitals to be intact to rebuild the nation.

Conclusion

The systematic targeting of the healthcare sector by the Assad regime to maintain power over his opposition and the larger civilian population during the ongoing Syrian conflict has resulted in the immense destruction of health infrastructure and the deaths of many medical personnel, jeopardizing the nation’s health for the near future. The regime justified these attacks on a “counter-terrorism” platform and will likely continue to do so as long as the conflict continues. The Syrian conflict reveals that although medical personnel and health infrastructure are said to be protected under international law, the policies of a regime and the harsh realities of war render the ink on a treaty ineffective. This issue is not confined to Syria, however; healthcare workers are under fire wherever there is an active conflict, from Afghanistan to Ukraine to Sudan. In the unfolding civil war in Sudan, local healthcare workers are facing many of the same threats as their Syrian counterparts as physicians are being targeted as “traitors” by the Sudanese army for providing care to opposition forces, while opposition forces are besieging hospitals.14 Healthcare workers are neutral players in conflict areas, and they need to be seen in that manner. It is essential to protect these populations from further harm, now and into the future.

References

- Laub Z. Syria’s War and the Descent Into Horror [Internet]. Council on Foreign Relations. 2021 [cited 2022 Nov 27]. Available from: https://www.cfr.org/article/syrias-civil-war

- Gharibah M, Mehchy Z. COVID-19 Pandemic: Syria’s Response and Healthcare Capacity. :14.

- Hill E, Triebert C. 12 Hours. 4 Syrian Hospitals Bombed. One Culprit: Russia. The New York Times [Internet]. 2019 Oct 13 [cited 2023 Jul 7]; Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/13/world/middleeast/russia-bombing-syrian-hospitals.html

- THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS OF 12 AUGUST 1949. 2020 Sep 6; Available from: https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/publications/icrc-002-0173.pdf

- Audi MN, Mwenda KM, Wei G, Lurie MN. Healthcare accessibility in preconflict Syria: a comparative spatial analysis. BMJ Open. 2022 May 4;12(5):1–11.

- The Survivors, the Dead, and the Disappeared: Detention of Health Care Workers in Syria, 2011-2012 [Internet]. Physicians for Human Rights. 2021 [cited 2022 Nov 14]. Available from: https://phr.org/our-work/resources/the-survivors-the-dead-and-the-disappeared/

- Conduit D. The Syrian Muslim Brotherhood and the Spectacle of Hama. Middle East Journal. 2016;70(2):211–26.

- Alhaffar MHDBA, Janos S. Public health consequences after ten years of the Syrian crisis: a literature review. Globalization and Health. 2021 Sep 19;17(1):111.

- Assault on Medical Care in Syria, United Nations Human Rights Council, September 13, 2013. Accessed November 27, 2022. https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/iici-syria/documentation.

- A Map of Attacks on Health Care in Syria [Internet]. Physicians for Human Rights. 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 5]. Available from: https://syriamap.phr.org/#/en

- Wong CH, Chen CYT. Ambulances under siege in Syria. BMJ Glob Health. 2018 Nov 27;3(6):e001003.

- Fouad FM, Sparrow A, Tarakji A, Alameddine M, El-Jardali F, Coutts AP, et al. Health workers and the weaponisation of health care in Syria: a preliminary inquiry for The Lancet–American University of Beirut Commission on Syria. The Lancet. 2017 Mar 14;390(10111):2516–26.

- Bashar al-Assad’s Opera House Speech, January 6, 2013 [Internet]. Carnegie Middle East Center. [cited 2022 Nov 27]. Available from: https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/50513?lang=en

- Khidir H, Khidir H, Owda D. Sudanese doctors should not have to risk their own lives to save lives. NPR [Internet]. 2023 May 24 [cited 2023 Jul 8]; Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2023/05/24/1177058026/sudanese-doctors-should-not-have-to-risk-their-own-lives-to-save-lives

The Public Health Student Association at Cal State LA, guided by Dr. Evelyn Alvarez, created a Little Free Library to promote climate literacy and encourage reading on campus. The project began after the pandemic disrupted earlier plans for a sustainability film festival. Students and faculty worked together to design and install the library, which features books on climate change, public health, and leisure reading. It was first placed in Simpson Tower and later relocated to the University Library for greater accessibility. Community members can take or donate books, and a survey with a QR code collects feedback to track its impact. The project highlights the importance of adaptability, collaboration, and creative public health interventions that support literacy, environmental awareness, and student engagement.